The promise of bioartificial organs

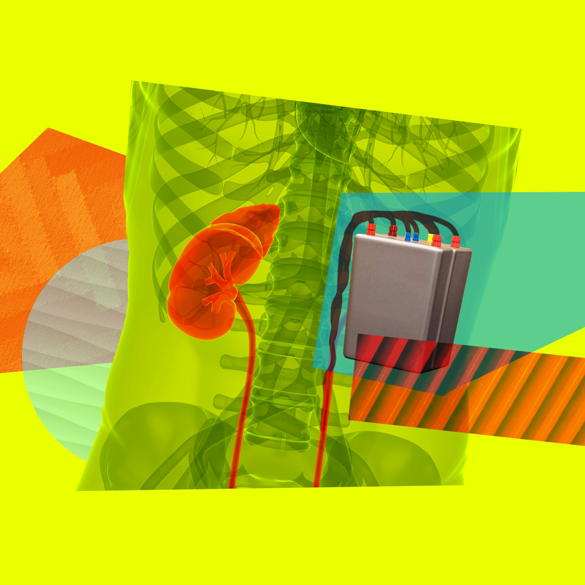

UCSF bioengineer Shuvo Roy and his team have created the world’s first bionic kidney. The coffee-cup-sized device includes a silicon nanotechnology filter to cleanse the blood, while living kidney cells grown in a bioreactor perform the other functions of a natural kidney. A bioartificial kidney could save kidney patients from being stuck on a dialysis machine for life – or dying while waiting for a rare transplant. But is the promise of such a life-changing device enough to convince investors to bring such a thing to market? We talk through the ethics of artificial organs.

— Dr. Bill Fissell“How do we get from here to making our innovations available to patients? Most of the products that are coming to market, they’re all about a half a billion dollars of investment to get there.”

Transcript

Transcript:

The promise of bioartificial organs

JOHN BRANDON BAYTON: Kidney disease can be very silent… until it’s reached its chronic level.

CATERINA FAKE: Hi, it’s Caterina. Roughly 37 million Americans are living with chronic kidney disease. That’s about one in seven.

BAYTON: I was diagnosed and immediately went on dialysis. It was like entering a little mini horror story.

FAKE: Almost 750,000 of these patients are facing end-stage renal disease where their kidneys no longer function well enough to sustain life on their own.

NIELTJE GEDNEY: What they said is, “if you don’t start dialysis within a year, you’ll be dead.” So I go to the dialysis clinic. There’s alarms blaring from the machines. Huge machines like refrigerators with tubes hanging out of them. Half of them look like they’re in comas. A lot of moaning. It was the most traumatic experience of my life.

FAKE: Dialysis machines can act as a kind of surrogate kidney, filtering waste from a patient’s blood. But the process isn’t quick or easy. A single session of dialysis can take three or four hours. Patients may have to go to multiple sessions a week. And dialysis treatment can go on for years – even decades.

BILL FISSELL: Time on the machine is scarce. You can’t spend 10 hours a day on the dialysis machine, or else: What are you living for? What are you going to do? You can’t check into the dialysis hotel for the rest of your life.

FAKE: There are alternatives to dialysis – organ transplant. Nearly 100,000 patients, the sickest of the sick, are waiting for a transplant. But fewer than one in five of them will ever find a kidney donor. Dr. Bill Fissell at Vanderbilt Medical Center knows all too well that the odds aren’t good.

FISSELL: And so patients gradually melt away. It’s like lighting a candle. And it just gets shorter and shorter and shorter until it’s gone. And so our goal is to get rid of the scarcity model.

FAKE: For the last 50 years, there’s been shockingly little innovation in dialysis. A dialysis machine is the size of a small refrigerator – but Fissell is working on an alternative.

SHUVO ROY: Our artificial kidney is the size of a coffee cup.

FAKE: Dr. Shuvo Roy works at the University of California San Francisco. Together, he and Bill Fissell are working at the intersection of engineering and biology to free those with chronic kidney disease from being tethered to a dialysis machine or pinning their futures on the organ donor lottery. They’re designing the world’s first implantable bioartificial kidney.

This coffee cup–sized device cleanses the blood, while living kidney cells operate just as an ordinary kidney would.

ROY: Making it mimic life, nature. Although I think we are all humble enough to know that nature is so much more sophisticated. To get to that level, it’s going to be a continuous learning process.

FISSELL: And I think we can do it. I think we’ve shown that we can do it. And I would like to see dialysis machines in a museum – as a relic.

FAKE: But is its promise as a life-changing device enough to bring it to market? Would access to a bioartificial kidney be universal, or simply another treatment highlighting the disparity between the rich and the poor? Would there be repercussions to the human donor market we can’t yet predict? And is an implantable device just another band-aid for kidney disease?

[THEME MUSIC]

FAKE: Hi, we’re back. Exploring the potential for a bioartificial kidney – where innovation goes back for more than a century.

ARCHIVAL: The evolution of the artificial kidney, the first true, vital artificial organ, is a story of the kinds of challenges that only the human body can present. And the kinds of creative solutions only the human mind could devise.

FAKE: The first dialysis machines came on the scene in the mid 1940s, during World War II. A Dutch physician named Willem Kolff used sausage skins, orange juice cans, and a washing machine to cobble together a device that could filter toxins out of blood. Twenty years later, the first patient received ongoing dialysis.

Vanderbilt nephrologist Dr. Bill Fissell sees dialysis as a phenomenal step forward … mistaken for crossing the finish line.

FISSELL: Fundamentally, it’s a minor miracle. This is the first technology, dialysis, that replaces a failed vital organ. Up until the 1970s, when dialysis really became a standard of care for renal failure, if your kidneys failed, you died. And I think that we were so impressed with ourselves for having done that, that we didn’t necessarily keep looking beyond.

FAKE: Has the process of dialysis improved in the past half century? Yes, but only incrementally.

FAKE: So what you’re saying is basically there has not been any innovation in kidney dialysis for like 50 years or more.

ROY: That is correct. And contrast that with a pacemaker defibrillator.

FAKE: Dr. Shuvo Roy is a bioengineer at UCSF. He’s also Bill Fissell’s partner on The Kidney Project.

ROY: It turns out the first pacemakers were also developed in the ’60s, and it was the size of a refrigerator. And today, a defibrillator, the size of a silver dollar. A dialysis machine has shrunk from the size of a large, big, clunky refrigerator to, at best, the size of an office under-the-desk-type refrigerator that it is today.

FAKE: Currently, the best treatment for kidney failure is a kidney transplant, but it’s hardly a simple process. Even successful procedures require immunosuppressive drugs with potentially lethal complications like blood clots and the risk of failure or rejection of the donated kidney. And that’s IF a patient can get a donor kidney in the first place. For most patients, dialysis is the only real option. And after five years of dialysis, a patient’s chance of survival is only 35%.

ROY: I’ll just put this in perspective if you look across cancers. Except for lung and pancreatic cancer, dialysis patients have a worse survival rate than all the other cancer patients.

FAKE: Dr. Roy has a PhD in electrical engineering. It’s a course of study that typically doesn’t involve kidneys at all. But 20 years ago, Shuvo Roy and Bill Fissell met at what, by all accounts, was a pretty boring office party.

FISSELL: So I was just kind of sitting there twiddling my thumbs, and I see a man standing over by the food table. And he’s not talking to anybody either. So I walk over there and say hello. And that person turns out to be Shuvo Roy.

FAKE: Fissell says that meeting was 100% serendipity – but resulted in a decades-long collaboration across the country.

Like Dr. Roy, Bill Fissell didn’t start out in nephrology. He majored in physics at MIT, and took a break from his studies to work as an EMT in Boston. Back then, dialysis was still pretty novel, and it was common for kidney patients to be transported to dialysis sessions by ambulance.

FISSELL: And I remember there was one woman, her first name was Mary, who we would transport three times a week. Mary was incessantly short of breath. She had enough bone demineralization, and so she wore a halo. She had a titanium bracket that was bolted to her skull that held her head up off of her shoulders, because her cervical vertebrae had collapsed.

FAKE: Seeing Mary regularly led to a kind of friendship between Bill and her – but then his schedule changed for a few months.

FISSELL: And then I got back on that shift again and picked her up, and she says, “Hi, Bill.” And we get in the ambulance, and we’re driving, and she asks me how I’ve been, asked me, “Are you still dating that girl?” And so on. And it was like a lightning bolt that this woman, in the context of crushing disease morbidity, has the personality and the interest and the liveliness to take interest in somebody else. If she can do that, I can do anything.

FAKE: Bill Fissell says he traces his revelation to that moment – seeing the desperate unmet needs of patients like Mary.

FISSELL: They’re soldiering on, they want a little more life, they want a little more time with their grandchildren. They want a little more time to read or write poetry or paint pictures. And we can do better. We have to do better for these people.

FAKE: So Bill says goodbye to physics and heads to medical school. But then, while he’s studying for his medical board exam, he has a eureka moment.

FISSELL: I was on call. I was in the hospital and I was dog-tired. And I was studying for my boards, and I was studying kidney physiology, because I wasn’t really all that good at it. I was staring at pictures of the kidney’s filters.

FAKE: The cells Bill was staring at were familiar. He had seen structures with the same size and shape while working on an x-ray telescope at MIT – that broke up light from distant galaxies into a small array of gold bars for astronomers to analyze.

FISSELL: And that’s when the first epiphany happened, that maybe we could change the underlying technology.

FAKE: The “underlying technology” fueling Fissell’s device is something called silicon nanotechnology. It’s the same technology that’s used by the computer industry to make microchips. The chips made ideal filters and with a few tweaks – potentially viable replacement kidneys.

FISSELL: And I put my pack on my back, and I went around the country looking for nephrology fellowships. And I think most places that I interviewed where I said my goal is to make an implantable artificial kidney using silicon nanotechnology. If I had announced to them that my career goal was to be a grizzly bear, they would have greeted me with no less astonishment and bemusement. It really was not a concept that was on anybody’s radar, technology development for kidney failure.

FAKE: Eventually, Bill meets Dr. David Humes at the University of Michigan, who was one of the very few people working on technology development for kidney failure. And he gets his fellowship and a mentor. Now years later, his idea is coming to fruition with Shuvo Roy.

ROY: So we call it the bioartificial kidney because it consists of a module that filters blood very much like the kidney does. But couple that with kidney cells. So we are mimicking the architecture and the function of a healthy kidney with the bioartificial kidney.

FAKE: Dialysis patients have to have extremely restricted diets. They even have to regulate how much water they drink, because they have no way to get rid of it except for dialysis, which washes their blood of two or three days’ worth of fluid and waste. In between those dialysis sessions, toxins in their blood can build to dangerously high levels.

FISSELL: It’s like a Cedar Point or a Six Flags roller coaster. The toxins build up and build up and build up and then suddenly boom, you drop.

FAKE: Fissell and Roy’s implantable bioartificial kidney has a simple, yet important goal: to mimic the natural actions of a real kidney. Their device operates with a patient’s blood flow, powered by the patient’s own heart.

ROY: So by using a bioartificial kidney that does continuous treatment, meaning removes toxins continuously, does the volume and electrolyte balancing automatically, allows the patient to eat and drink more normally.

FAKE: And no longer the 12-hour sessions, no? Eating and drinking, drinking normally, you can travel.

ROY: That’s right.

FAKE: And it sounds as if it’s transformative, completely transformative.

FAKE: And it’s engineered with filters to avoid triggering blood clots, a challenge for all patients with long-term implants. Another key benefit – its cost.

ROY: Dialysis and end-stage renal disease in this country is a very unique disease in the sense that it’s the one condition that’s paid for by Medicare, no matter what age you are. So the cost of hemodialysis to Medicare is around $90,000 per patient annually. And if you look at the total bucket of costs, it exceeds $35 billion. It’s about 7 percent of Medicare for 1 percent of this population.

FAKE: Wow.

FAKE: So say that a bioartificial kidney became the norm. How much would that lower the costs?

ROY: If we were to scale up production and take advantage of all the economy of scale, we could provide the bioartificial kidney to “the market” at less than $20,000.

FAKE: Wow, OK.

FAKE: But scaling up comes with its own set of challenges and risks. Dr. Bill Fissell says pushing the bioartificial kidney beyond human trials will be expensive.

FISSELL: We have a big valley to cross, the so-called valley of death. When we’ve made this seminal, the germinal establishment that we can do this. How do we get from there to making our innovations available to patients? Most of the products that are coming to market, they’re all about a half a billion dollars of investment to get there.

FAKE: And who has that money? Selling the idea to a giant in the industry worries Bill Fissel.

FISSELL: There is a kill zone around the giants in the field, I think. There’s always a risk when you lose that governance and control of the technology, that it might be sold to some entity that wants to kill it, that wants to put it on a shelf.

FAKE: After the break, we’ll talk with patients living with end-stage renal disease. Not only about their hopes for how a bioartificial kidney could transform their lives, but about what other questions we should be raising before widespread adoption of such a device.

[Ad Break]

FAKE: Hi, it’s Caterina, and we’re back talking about the bioartificial kidney, and its potential as a breakthrough for kidney patients currently relying on dialysis. Right now, it’s hard to see a downside – unless you’re part of the multibillion dollar dialysis industry, who might see their business model become obsolete. Or if you just don’t have time to wait.

NEWS CLIP: The coronavirus outbreak has brought dialysis services in New York to a breaking point.

FAKE: Patients with chronic kidney disease are already vulnerable with a life-threatening illness, and recently have been hit hard by COVID-19.

CLIP: Now major hospitals across New York are reporting shortages of crucial dialysis equipment.

FAKE: Although COVID is a respiratory disease, it can cause what’s known as a cytokine storm in patients, a potentially fatal side effect that overwhelms a patient’s kidneys.

NIELTJE GEDNEY: I am not an alarmist. I’m probably one of the calmest people you’ll ever meet. I’ve actually almost had panic attacks lately.

FAKE: Nieltje Gedney is a dialysis patient living in West Virginia. We spoke during the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak. Receiving dialysis in large facilities with dozens of other people could also easily expose patients to the virus.

GEDNEY: It’s very frightening. And the kidney population often have comorbid diseases like diabetes with their kidney disease. So we’re very vulnerable. And for us, it’s almost certainly a death sentence.

FAKE: Nieltje’s advocacy for improved kidney treatment options predates COVID-19. She’s an officer of Home Dialyzors United, speaking for the 7% of patients who are able to do dialysis in their own homes. The first time she heard about the transformative potential of the bioartificial kidney, she was at a conference listening to a lecturer whose name you already know: Dr. Shuvo Roy.

GEDNEY: I was blown away. I had just started dialysis. I knew very little about it except that I did not want a transplant.

FAKE: For Nieltje a transplant would mean taking immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of her life and an unpredictable outcome.

GEDNEY: And here he was talking about no immunosuppressive drugs, something that was minimally invasive. And I went up to Shuvo afterwards, and I said, “Oh my gosh, you have just given patients so much hope.” And he looked at me, and he said, “This isn’t hope, this is a reality.”

My dream, which I think represents the renal community, is patient choice. There will always be patients who want say, a living donor organ, maybe from a family member. You have someone like myself who would never take a living organ, but would take an implantable. When it comes to dialysis. Again, there’s no one machine that works for everybody.

FAKE: While Nieltje’s excitement about new treatments is about patient choice – for others, it’s about one thing: peace of mind.

JOHN BRANDON BAYTON: It would really, to me, be the ultimate freedom. It would alleviate recurring fears.

FAKE: John Brandon Bayton has had every form of treatment available. Dialysis in clinics, dialysis in his home, and two separate transplants. The first one failed.

BAYTON: And so it’s always in the back of your mind that this could fail again. I mean, I know some people who are on that third and some on their fourth transplant.

FAKE: John is based in Washington, DC, and was diagnosed in his early 30s when he ended up in the ER and went directly to dialysis. For somebody who’s been through as many treatments as John, the bioartificial kidney represents something new: hope.

BAYTON: Fingers crossed it doesn’t happen, that the transplant I currently have fails, that there is a more viable alternative than waiting on a waiting list and praying.

FAKE: As hopeful as John is, his imagination is able to play out other scenarios. As a self-proclaimed sci-fi nerd, it’s not hard for John to see how the noble intentions behind the bioartificial kidney could be hijacked by some sort of supervillain.

BAYTON: The supervillain version is, only those with influence and or the necessary funds will have access to it. And people in vulnerable communities, people of color, immigrants, people who may not have the financial means to be put first in line are going to be adversely impacted by it.

FAKE: Remember, Bill Fissell and Shuvo Roy anticipate their bioartificial kidney being far more affordable than dialysis … once it scales. Until then, there are valid concerns that early prototypes might only be available to the well-off.

KRISTEL CLAYVILLE: I think there’s a hopefulness among medical professionals and biotech developers that if we can create enough things, then we will be able to solve our problems. And I think, I disagree.

FAKE: Dr. Kristel Clayville is a chaplain at the University of Chicago Medical Center who works with kidney transplant patients. She’s also got a PhD in religious ethics, which gives her a unique perspective on the bioartificial kidney.

CLAYVILLE: It solves a scarcity problem. But of course, you still have the fact that transplant teams want to put kidneys into good patients, people who are going to be able to work with them and maximize their own survival. And I don’t think that the artificial kidney changes that dynamic.

FAKE: Kristel’s relationship with the kidney transplant patients she works with is intimate. She spends some of her time in committee with surgeons and transplant teams working to evaluate the donor wait list, but she also counsels patients awaiting transplants. Or those who have just received a kidney from a donor.

CLAYVILLE: They have any number of questions like, what will my new life be like? I’ve been tethered to this dialysis machine for a very long time. And then there are questions that are more existential, like, “I’ve just realized that somebody has to die for me to live.” And then if they have living donors, there are other kinds of concerns that pop up. Like are they asking too much? Can they ever repay it? Will they feel like they owe this person something more than they could ever give back?

FAKE: She believes a bioartificial kidney could help resolve these and other questions without clear answers – like the debate about organ transplantation from religious groups who actively oppose it. Some object to transplants from deceased donors. Others protest that it might impede the life or hasten the death of the living donor.

CLAYTON: I think artificial kidneys help us, in religion, reframe how we think about organ transplant. It’s not necessarily just about definitions of death, right? But if the religious traditions can start thinking about organs as not scarce, then potentially there’s a way to move that conversation to thinking about allocation and access to transplant.

I mean I think the utopia is trying to decrease the need for kidney transplants by actually treating kidney disease earlier, right. And then there would be potentially a decrease in the number of people who needed kidney transplants as this sort of heroic intervention.

FAKE: Meantime, the data shows kidney disease is only on the rise – with increased incidence of the leading causes: diabetes, and high blood pressure. These findings only heighten the value of early recognition of kidney disease and preventive strategies.

ALVIN MOSS: And what we have had is a disease-oriented focus rather than a patient centered focus. And the problem is that dialysis makes money, and it decreases the incentive to try to really prevent people from developing kidney disease.

FAKE: Dr. Alvin Moss is director of the Center for Health, Ethics, and Law at West Virginia University. And Chair for the Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients.

MOSS: What about a bioartificial kidney? I am sure people will come out of the woodwork to think this is a fantastic idea, knowing that there are 100-, 110-, 120,000 new patients a year. Huge market. We can charge an arm and a leg for it. And we’re going to then totally miss the emphasis on prevention that we really should have. It’s much easier to come up with some new technology, very expensive technology that makes some people a lot of money but doesn’t really comprehensively deal with the problem.

FAKE: In his 40 years as a nephrologist, Dr. Moss was the medical director of a dialysis unit for two decades – where he watched many of his patients suffer. That led him to do a fellowship in medical ethics and then to hospice and palliative medicine where he helps patients at the end of their lives who voluntarily make the decision to stop dialysis.

MOSS: I mean, I have patients who would love to not be saddled to a dialysis machine for four hours, three times a week. So if the bio artificial kidney helped them feel better, that would be wonderful.

But it’s not as good a solution as a national program that identified 80-90 percent of people who have the potential of going into end stage kidney disease, and stopped the progression of their disease so that they would never need dialysis. That would be even better.

FAKE: Coming up on Should This Exist: kidneys aren’t the only organs being recreated by scientists. Researchers are working on artificial hearts, livers, lungs, and more. Is there something lost when humans become more and more bionic?

[Ad Break]

FAKE: Hi, it’s Caterina, and I’m talking with Dr. Shuvo Roy of UCSF about the long view – not just for the bioartificial kidney, but for other similar devices as well.

FAKE: Do you ever think about how, you know, building these kinds of devices might lead us towards being, kind of like more technological people, being more, you know, I don’t know, cyborgs. Do you think about that?

ROY: I don’t know if you’re familiar with the old Six Million Dollar Man, $3 Million Woman movies or shows. So people have come to me and in the emails that I’ll get, I’ll get things, you know, how is the bionic kidney? And the same platform that allows us to build the artificial kidney can be applied to other organ systems. So yes, once you think in terms of combining cells with electronics, with mechanical components, you create more and more bionic organs.

And a few years ago, there was actually a program in the UK on television where they actually went around the world asking for prototypes from different groups, companies and labs to create what they called at the time was the most complete artificial human being.

FAKE: For the record, the series was called, “How to Build a Bionic Man?”

CLIP: In London, packages are arriving from all over the world. That box has the hand that goes with my elbow. Aahh. OK, let’s have a look at the hand. Nice. Leading biomedical innovators have donated the most sophisticated prosthetic parts available. No one has ever attempted to combine them into a single functioning body before.

ROY: So from our lab, they got a prototype model of the kidney. From somebody else, they got an electronic eye, from somebody else they got a heart and a lung. And they’re able to put all that together for the TV show and show that, you know, yes, it is possible to think at least more bionically. Whether that’s going to happen in our lifetime, I don’t know.

FAKE: Does that appeal to you? I mean, it sounds like an interesting show, to be honest.

ROY: So as an engineer, I think it’s fascinating, because you’re bringing, you know, fundamentals, mathematics, physics, chemistry to bear on problems in creating something that did not exist before, making it mimic life, mimic nature. Although I think we are all humble enough to know that nature is so much more sophisticated. To get to that level, it’s going to be a continuous learning process. We are basically, you know, at the beginning of that cycle.

FAKE: We don’t know what we don’t know…

FAKE: Though bionic humans may become commonplace someday, Shuvo Roy and his collaborator Dr. Bill Fissell have concrete next steps to take for their bioartificial kidney. At the end of last year, their project marked a major milestone. They successfully implanted prototype bioartificial kidneys into pigs without immune reaction or blood clotting. The next step is human trials, and there’s already a long list of patients ready to participate.

FISSELL: I’d like to see the first of our devices tested in the human patient this calendar year. In five years, I hope that we’re a commercial entity that patients can select, if it suits them.

In 10 years, I hope that we’ve got a technology available where, when a patient develops kidney failure, comes to the doctor’s office, they can walk out with a real kidney from a donor – or a fake kidney that we designed and marketed.

FAKE: Bill Fissell started his work by hoping he could relegate dialysis to an exhibit at a museum. So it’s funny – or maybe just fitting – that he wants the same thing for himself.

FISSELL: Twenty years from now, I hope that I’m an irrelevant footnote in history, to be honest with you. I hope that developments in medical science put me and everything I’ve done out of business. And just render us an odd historical footnote.

FAKE: Look, I don’t get to decide Should This Exist? And neither does this show.

Our goal is to inspire you to ask that question – and the intriguing questions that grow from it.

LISTENER: What I say is all the rich people can buy their bionic kidneys to leave more kidneys for people that can’t afford them. And then everybody wins.

LISTENER: My dad is on dialysis. This could change people’s lives. It could change my life.

LISTENER: I am not afraid of bionic organs. We already have them. I don’t see why the kidneys should feel left out.

LISTENER: What are the trials? Is the testing safe? What are the long-term side effects? And how do we even know?

LISTENER: The dialysis industry is huge? If this really solves dialysis, I wonder if the dialysis industry is going to get in the way of it.

LISTENER: Is this the first step of creating an artificial human being?

LISTENER: How could we improve upon the human organs we already have? Is there a way to make a kidney more efficient by making it bionic? Is there a way to make a liver better by making it bionic?

FAKE: Agree? Disagree? You might have perspectives that are completely different from what we’ve shared so far. We want to hear them. To tell us the questions you’re asking go to “shouldthisexist-stage1220.mystagingwebsite.com” where you can record a message for us.

And join the Should This Exist newsletter at shouldthisexist-stage1220.mystagingwebsite.com.

I’m Caterina Fake.