Grandma, here’s your robot

Is it the loneliest idea you’ve ever heard? Or an ingenious hack that helps human caregivers be more attentive and empathetic? You might have these questions when you meet the robot caregiver who roams the halls at this retirement home, doing basic tasks for residents and keeping them connected. But is eldercare something we want a robot to do? Roboticist Conor McGinn from Trinity College Dublin actually moved into a retirement home in Washington, DC, to gain a deeper understanding of what residents might want from a robot. The answer surprised him, and it prompts deeper questions: As humans, what responsibility do we have toward our elders? When we fail them, should robots close the gap? And is that the future we want for ourselves?

— Dr. Conor McGinn“When you go into a retirement home, often you see the people sitting in front of a television. A robot like Stevie — it’s not as good as a person, but it’s probably better than a TV.”

Transcript

Transcript:

Grandma, here’s your robot

CATERINA FAKE: Hi. It’s Caterina. For a thousand years and more, storytellers in every culture have imagined mechanical beings.

In the Iliad, Homer described how the god of blacksmiths whipped up a few golden handmaidens to help him do his work.

Robots were usually good to humans in the tales the ancients told. Of course, they weren’t called robots. The word “robata” – meaning “forced labor” – was first used in 1920 in a Czech play about artificial factory workers that rebel against their human masters, and kill them. Somehow, in the 20th-century imagination, robots turned bad.

ROBOCOP: Please put down your weapon. You have 20 seconds to comply.

DICK JONES: I think you’d better do what he says, Mr. Kinney.

FAKE: There are a few exceptions. This guy is so adorable and non-threatening, he even took a mechanical shuffle down Sesame Street back in the late 1970s.

SESAME STREET: R2D2, this is called a banana.

FAKE: “Loveable robots” like R2D2 exist, largely thanks to the legendary science fiction pioneer Isaac Asimov. In the 1940’s, Asimov laid out three laws for robots to peacefully coexist with humans in a short story called “Runaround.”

ISAAC ASIMOV: A robot may not harm a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

FAKE: Asimov’s laws have guided real roboticists ever since. And we’re now living in a robot-filled world. An estimated two and a half million robots work in factories. Other robots make sushi, perform heart surgery, and explore volcanoes.

In the 21st century, robots have become uncannily common. But there are still new frontiers they’re only starting to explore. One of those places is eldercare.

CONOR McGINN: You know, when you look at the healthcare industry, we see huge shortages, as you know. So there’s a demand for far more caregivers, because there’s far more older people that need extra support.

FAKE: Conor McGinn is an engineering and robotics professor at Trinity College in Dublin. He says: Just do the math. About one in every seven Americans is over the age of 65. By 2040, that number will be one in five. And the number of people over 85 will more than double.

McGINN: But we’re also seeing the average age of caregivers increasing, meaning that many of the current care workers are coming into retirement age. So as a result: this huge deficiency of care staff. And what we need to do is develop technology that enables people to do more with less.

FAKE: The math may check out, but there’s a deeper question at play here. As people live longer, lonelier lives, are robot caregivers the saviors we need? If we leave this task to the robots, what could go wrong? And what does it say about us?

[THEME MUSIC]

FAKE: It’s Caterina, and we’re back.

FAKE: This is very beautiful … the proximity to the park.

FAKE: I recently visited this wooded neighborhood of Washington, DC, to see what was going on at Knollwood, a retirement and nursing home that was created by Army widows after World War II. And before we go any further, I should tell you, this was recorded in February, right before COVID made visiting a nursing home dangerous to all involved.

STAFF: Excuse the creaking door…

FAKE: It feels kind of like a college campus. It really does.

FAKE: Knollwood is now a nonprofit, 300-bed retirement home for military officers and their families. Nothing about this bucolic place, with its bingo nights, upholstered curtains and early-bird suppers, would suggest that there’s any high-tech innovation going on.

STEVIE: Hi.

FAKE: But…

STEVIE: How are you? My name is Stevie.

FAKE: This is Stevie. A robot who has lived in residence here with his creator, Conor McGinn, an engineering and robotics professor at Trinity College in Dublin.

FAKE: Hi! Great to meet you. Caterina Fake.

McGINN: Catarina, lovely to meet you.

FAKE: I met Conor in the original Knollwood building, a kind of Tudor affair with dark walnut paneling from a Vanderbilt mansion. It’s mainly used now for events.

FAKE: It’s very woody and full of antique furniture and so it does not seem particularly techy. It’s very homey.

FAKE: Conor has lived in this building with his team for months at a time while piloting his robot, Stevie.

McGINN: I can say I’m probably the youngest resident of Knollwood.

FAKE: And what made you choose this place rather than other places that you could have been working?

McGINN: I’ve been to Japan, South America, and then most of North America – from Silicon Valley to here. So really what I guess we were looking for in a place is the kind of facility that had the technological infrastructure that could support a robot so, you know, really good WiFi was needed. Also, we wanted to have residents that weren’t going to be scared or put off by the idea of a robot.

FAKE: Knollwood even has a full-time manager in charge of innovation and technology. It all added up to a place where Conor McGinn could settle in for a long-term relationship to develop his robot.

FAKE: Tell me a little bit about how long you’ve been developing Stevie.

McGINN: I think many engineers are inspired by things that happen to themselves, and what happened to me was my grandmother. She moved into a nursing home. While the staff there did their best, people didn’t have an awful lot to help them.

And at the time I was an engineering student, and you know, I was seeing exciting new things happening, things like robotics and AI. And I just felt like now we’ve got to do something here.

FAKE: I, too, had an aging grandmother, and I worked in nursing homes when I was young, starting when I was 15, and I was responsible for a lot of the patients, who were incapable of kind of feeding themselves, to feed them.

McGINN: I worked at a nursing home for a number of weeks when I would have been maybe 16 or 17 as a part-time job. I guess it’s a profession I’ve just developed so much respect for.

FAKE: That’s why Conor McGinn’s greatest hope is that Stevie – or rather, a fleet of Stevies – will improve the lives of nurses, orderlies, and other caregivers, so they can better handle their jobs, with less stress. And at the same time bring some joy to people who are on in years.

STEVIE: N 42. N-4-2.

RESIDENT: Oh I have a bingo.

STEVIE: We have a bingo.

FAKE: Conor McGinn and his team have spent so much time here living at Knollwood on and off for a year. They’ve been asking the question of both staff and residents: what kinds of tasks should a robot do, and not do? Should it do medical monitoring? Run errands? Be a companion?

At the moment, Conor is focusing in on social tasks.

McGINN: So running something like a group brain exercise game. Basically, it’s a little like Jeopardy! So the robot was front of house, and the robot was basically asking questions. Even bingo, where you might need to call the numbers out at the same time as helping the residents. And as a result, the staff can be like yo-yos. And what we’ve seen is that by having the robot do that sort of front of house, kind of organizing, running the show, so to speak, the staff are able to take a breather. They can be the ones laughing.

FAKE: They’re supportive. That’s super interesting.

McGINN: It just flips it on its head. And the staff enjoy it. And then when the staff are happy, the residents…

FAKE: …are happy.

McGINN: They build on that energy.

STEVIE: G 47, G 4-7.

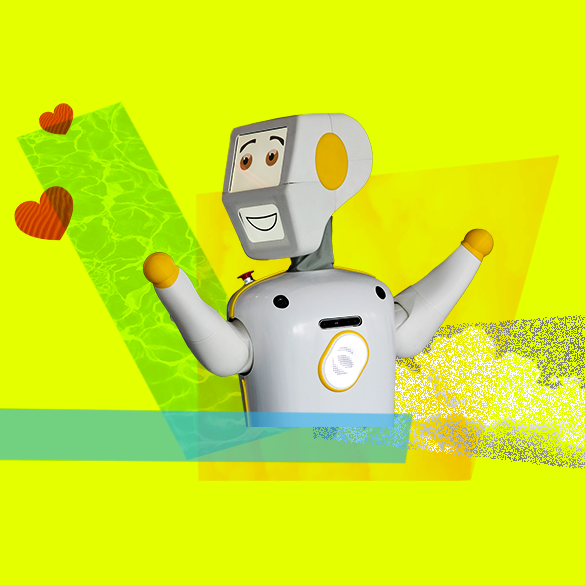

McGINN: So Stevie is about four-foot-five tall and moves around on wheels, but its body is sort of shaped like a person. So its face is very much, you know, kind of a mix between a cartoon and a child’s. That was the sort of the inspiration that came there. We wanted this to be something that, you know, people smiled when they saw.

FAKE: Stevie’s face has two screens. One for his eyes and one for his mouth. His expressions are simple like emojis, but they can be changed in infinite ways, since they’re software-based.

McGINN: It took us a long time to get the design right on that.

FAKE: And then there’s a screen on the chest.

McGINN: So the screen on the chest isn’t there permanently. So we have an attachment that if you did want to put a tablet on the chest, you can do so. So there’s cases that where, for example, people are hard of hearing, they might like to see subtitles of what the robot’s saying.

FAKE: OK.

McGINN: Or, for example, if you wanted to do a Skype call or where you want to see somebody, then, you know, having the screen can be helpful.

FAKE: In case you’re picturing something shiny and metallic like the Iron Giant, don’t. Stevie looks softer, mostly white. And although there’s nothing particularly male about him, he’s a he. In a world where something like 90% of AI assistive technology looks or sounds female, Conor McGinn wanted to buck the stereotype. Oh, and Stevie does have arms, though calling them “arms” might be a little generous. They look a little like bowling pins.

McGINN: I guess the arms being somewhat simplified is quite intentional. We didn’t want people to develop the expectation that wasn’t going to meet the reality. So we felt that like by designing it in such a way that the arm still had purpose. They’ve proven very effective in extenuating emotions.

FAKE: They’re gestural.

McGINN: Yeah, gestural, so they can point to things. But it’s helped ensure that we’re not deceiving people.

FAKE: Deceiving people. That phrase caught my attention. So here’s the thing. Conor will tell you there are sticky questions that arise when you’re talking about employing a robot to help a vulnerable population. And maybe, a cognitively impaired population. Especially when that robot looks and talks kinda like a person.

McGINN: We want to make sure that people understand the degree of autonomy that the robot has. So when the robot is in a room, if it’s being autonomous, we’ll tell them it’s being autonomous. If it’s humans controlling it, we tell them the human’s controlling it. So there’ve been times where we’ve tested it from…. We’ve actually had people in Ireland controlling the robot.

So if you’re working a 2 a.m. shift here in D.C., that’s not a shift that you’re going to want to draw from a hat. Most people would prefer to work, you know …

FAKE: During the daytime.

McGINN: And we think that potentially a robot was capable of being situated in an environment, then, you know, perhaps, you know, people who are working in one time zone could control a robot in a different time zone and manage the calendars more efficiently.

FAKE: Whether he’s controlled by someone in the room or across the ocean, Stevie could do a lot of things. At the moment, he does just a few.

[KARAOKE SINGING]

FAKE: Stevie was quite a hit at karaoke during his stay. Karaoke night has been popular for a few years at Knollwood, thanks to a resident named Phil Serriano, who runs it twice a month.

STEVIE: OK, Phil, let’s do this.

PHIL SERRIANO: It’s our theme song.

FAKE: Phil was excited to work Stevie into his act. He figured it might encourage people to join in, if Stevie roamed around with the lyrics on his belly. Colin showed us a video of the last event they did before Stevie headed back to Ireland. At the end, people were hugging Stevie and blowing him kisses.

[KARAOKE SINGING]

FAKE: Come on down.

FAKE: Conor and I sat down with Phil, and two of his karaoke regulars – Marge Tadero and Lee Frick – to talk about spending time with a robot.

MARGE TADERO: Stevie is as cute as a button.

LEE FRICK: And he’s a lot of fun with karaoke.

SERRIANO: At first people were a little bit hesitant. But, you know, the eyebrows were raised, you know. And after a while, he was just a natural part of the scenery. So he was one of us. He was one of us.

FAKE: Do you think it’s important for robots to have a personality?

FRICK: Oh yes. I definitely think so. Yeah.

TADERO: And he had a wonderful personality.

FRICK: He has a nice personality.

FAKE: What were some of the things that you didn’t like or that you thought could be improved in the robot?

SERRIANO: He’s off key.

McGINN: We’re still working on that.

SERRIANO: Yeah, we gotta work on his pitch.

FAKE: And with that, our three guests headed down the hall to the annual Mardi Gras party, where last year, Stevie led the conga line draped in Mardi Gras beads.

I asked Conor about this phenomenon – this connection that Phil, Marge, and Lee clearly have with the robot.

McGINN: The thing is, they know that most of what’s going on there is being controlled by a person. But there’s a suspension of disbelief there that is a little bit like, you know, going to Disneyland and seeing Mickey Mouse. You know, it’s a character that you form an attachment with. You know that there’s a person in the suit, but it’s the character that you associate a meaning and value to.

FAKE: When you first arrived here, what were your expectations for what the robot would do? Like what kinds of tasks? ’Cause I’m sure that karaoke, you know, assisting in a karaoke program was probably not on your list.

McGINN: Definitely not. A quote that always goes back to Henry Ford, I don’t think he ever said it, but he said, “If I’d have asked the people, they would’ve said you would have liked a faster horse.” So when we’ve done –

FAKE: Not a car. You just want faster horses.

McGINN: Exactly. Because when you think of a robot, we think of factories. We think of like high, ultra-high efficiency. We don’t think of the quality of interacting with them because like, you know, traditionally they’ve been separated from people. And where we have seen interaction, it usually ended pretty badly. You know, something of Terminator like this sort of science fiction?

FAKE: Yeah, sure.

McGINN: But what happened was that when we did focus groups, and we thought things like delivery tasks would be top of the list, but people were saying, actually, you know, we like that it makes us laugh. You know, we like that it listens to us. And when I ask it a question, it answers me back.

FAKE: They didn’t want to send it off to retrieve packages.

McGINN: The things that we were hearing more frequently related to the experience of interacting with it. You know, I volunteer to go down and read to people with dementia twice a week. Could the robot do that?

FAKE: The answer is yes. A robot could do that. But should it? Should we assign reading and other social tasks to robots? Conor McGinn says “yes.” He believes this is the kind of task Stevie is perfectly suited for. He knows there are critics who disagree, who think that robots threaten to take away the most important aspect of care: the human touch. But Conor says those fears are largely based on a mismatch between what we imagine robot eldercare might look like, and what it will look like.

[BREAK]

FAKE: Hi. It’s Caterina. We’ve been spending time with Conor McGinn, talking about the tantalizing potential of robotic eldercare. He envisions a future in which robots could take on a sort of supporting role in nursing homes.

And in the time of COVID, the advantage of caregivers that can’t get sick is all too obvious.

But it also opens all sorts of questions. Is this really the best we can do for our aging population? Is there a lack of dignity in having to get your bedtime stories from a machine?

This world of robotic elder care may sound far off, but it’s not. It’s also not new. Let me tell you about Joseph Engelberger, better known as the Father of Robotics.

BRITISH ’60s NEWSREEL: Unimate, a machine that can reach out to seven feet and perform a multitude of tasks in a factory as skillfully as a man but without getting tired.

FAKE: The Unimate was the very first commercial robot. A robotic arm, really, that General Motors bought from Joe Engelberger and his partner George Devol in 1961. The Unimate’s job was to lift and stack hot pieces of metal. It absolutely revolutionized industry. But Joe Engelberger’s bigger dream was to create a robot to improve life for seniors. Only he didn’t just dream it, he built it. A prototype, anyway, named Isaac, after Isaac Asimov.

ENGELBERGER: The nursing home is the kiss of death for an older person. The last thing they want is a nursing home.

FAKE: That’s the late Joseph Engleberger himself, speaking at Carnegie Mellon University.

ENGELBERGER: Today in the United States, the fastest growing age is 85. Almost everyone at 85, in that range, is disabled in some way. So that’s a market.

FAKE: Engelberger’s vision was different from Conor McGinn’s – a service robot for home, to keep older people independent and out of nursing homes. His company had already built robots for hospitals. Now it would rent robots to older folks, reducing the need and the exorbitant cost of human caregivers.

ENGELBERGER: Well, it’s going to fetch and carry. It’s going to prepare meals. It should clean house, should monitor vital signs, and report on to a remote human doctor. Someone sitting there watching television has to go to the bathroom more often than a younger person does. If they’d had a robot instead, who cares how often you ask a robot to take you to the bathroom? It’s the kind of relationship that would help.

FAKE: The way Engelberger saw it: the less human the robot, the more dignified the experience. These helpers weren’t there to tell stories or sing karaoke. They existed to do the mundane chores one might be embarrassed to ask a human helper to do. It’s embarrassing to ask to go to the bathroom, over and over. Making the robots impersonal would take the humiliation out of the equation.

Joe Engelberger finished his talk by expressing his frustration that he hadn’t found support for his eldercare robotics program, but that he knew it would one day happen – with or without him. Because the market was just so big and the need too great.

What he didn’t exactly predict is just how attached we might get to our robot helpers. It’s human nature to assign human-like qualities to our tech. We name our phones, our WiFi networks, our cars. Connecting on an emotional level with machines is incredibly common. And if that seems silly or sentimental, you might think again after talking to the men and women who work in the military’s bomb squads.

CARPENTER: Robots are a critical part of their everyday toolset because they render any kind of unexploded ordnance safe.

FAKE: Julie Carpenter is a research fellow in the California Polytechnic Ethics + Emerging Sciences Group.

CARPENTER: And that could be IEDs, it could be mines, nuclear weapons, chemical weapons, anything. And the robots keep them safer, because they can operate them from a geographical distance.

FAKE: A few years ago, Julie wanted to find a way to study how human beings react to working in close collaboration with robots. She knew that if any group had established a relationship with robots, it would be the bomb squad.

FAKE: I mean, it sounds like a super high-pressure situation, extremely tense. This is live on the battlefield. And they are working with the robots like team members, right?

CARPENTER: Well, so that’s a good question. These people are highly, highly trained. Their training is ongoing because of the nature of their work. And so while they did not regard the robots as a team member at a human level at all – if it’s a decision where a robot is going to be harmed or a person, it’s absolutely going to be the robot every time. And they 100 percent, when I asked them, would define the robot as something that is a machine or a tool. However, I found that some of their interactions were indeed social – that could go from anything from naming the robot to treating it in a pet-like way in little rituals.

FAKE: Though Julie Carpenter didn’t see it personally, she has heard stories about the Explosive Ordnance Disposal specialists, or EODs for short, having Purple Heart ceremonies for their robots. And funerals.

CARPENTER: And even these EOD robots, if they are not designed to look human, it still gives us some cues that seem to trigger that sense that the thing has some lifelike qualities to it. People would talk about how the responsibility in particular of taking care of and maintaining this critical tool. They’re like: “you know it is a tool, but sometimes taking care of it and so forth makes it feel more like you’re sharing a sense of history and narrative with this other thing.”

FAKE: But is anthropomorphizing our tools healthy? Or is there a downside we’re not seeing?

THOMAS ARNOLD: We have a robot that can actually simulate crying.

FAKE: That’s Thomas Arnold. He’s a researcher at the Human-Robot-Interaction Lab at Tufts University, with a background in philosophy and religion. He thinks a lot about how robots can draw our emotions. And manipulate them.

ARNOLD: You can elicit people’s sympathy remarkably easily, more easily than you would think, let’s put it that way.

FAKE: Robots, he says, are giving us insights into human instinct. And those insights should give us serious pause about how and whether we think robots are appropriate for our elders.

FAKE: I mean, there’s a lot of unspoken ethics and norms in human interactions, especially in our intimate relationships with others. Can roboticists really get that right in the building of the robots?

ARNOLD: You know maybe getting it right for robots is not to try to replicate that, but to have something that is different but complementary and doesn’t try to deceive or exploit or manipulate by trying to represent itself as other than what it is.

Whether in the case of an automated wheelchair, that might be a good example of something that could reliably and even interactively, with some basic natural-language commands, that might be something that both gave a user a sense of autonomy, but was also assistive without trying to be anthropomorphic, without, you know, having a face or something like that.

FAKE: I asked Thomas Arnold if he felt there were pitfalls in a future with robots as caregivers.

ARNOLD: I do. I think there can be patterns of thinking of eldercare residents as kind of objects to be cared for and not agents who are, you know, still making meaning of their lives and still trying to engage and create. Robotic systems that could kind of encourage that kind of challenge without being overwhelming, I think would be humanizing because the robot is not trying to assume functions that it really has no place assuming. It’s actually engaging and challenging and eliciting more vitality.

FAKE: Because you don’t want it to end up with a kind of obsolescence of human caregiving.

ARNOLD: Absolutely not. No. The kind of pattern, or at least one thing that I’m concerned about, is the robot as a symbolic distancing, a symbolic prophylactic against death and disease and deterioration that sends the message under the guise of this robot is fully-capable, and we have need. That really, it’s a rationalization for, so we’re gonna let the robot do it. And we might visit, or we’re not going to necessarily invest the time and the hard work into designing eldercare facilities that really improve quality of life the way that they could, out of a sense that it would just be neater and less messy not to have to face that.

FAKE: Thomas Arnold says that one way to ensure a path forward that respects the dignity of older people is for roboticists to involve older people and their caregivers in the development of the technology. Something Conor McGinn has gone to great lengths to do.

But I can’t shake Thomas’ concern that assigning eldercare to robots might just be driving our aging populations farther out of sight. Would automating parts of the caretaking process just make it easier for us to look away?

[Break]

FAKE: We’re back with roboticist Conor McGinn, creator of Stevie. Conor reminds us that when we think about whether we want robots involved in the care of our aging relatives, we need to remove our rose-colored glasses, and think about how good a job we humans are doing, right now, without robots.

We’ve all heard chilling stories of abuse and neglect in nursing homes, and COVID has brought more of these to light. Robots aren’t going to make this a dystopia – the picture is pretty dystopian now. And even at the most expensive private facilities, there’s a machine in place that in Conor’s view is doing our seniors harm.

McGINN: One of the common experiences that I’ve had personally is that when you go into a retirement community, or an older person’s house, very often they’re sitting in front of a television. Statistics suggest that actually older people are more frequent use of screen-based technology than younger people. As a result, you could become pretty understimulated because of it. I think that a robot like Stevie, even though I don’t think that we’re claiming it’s as good as a person, but we would say it’s probably better than a TV for providing that kind of interaction.

FAKE: So if you think about it, potentially what Stevie is doing is replacing television, not replacing people.

McGINN: That’s how we view it. So one of the things we did was we made Stevie tell the residents in the memory care facility here an Irish folklore story. So maybe a five-minute-long story. And Stevie’s voice is pretty monotone. It’s not able to carry a lot of the emotions that normally a storyteller would say. So I was personally a little bit skeptical.

STEVIE: “Take my magical white horse, she told him. Do not get off this horse. And do not let your feet touch the ground.”

McGINN: But interestingly, after nearly four or five minutes in the story, when the hero fell off his horse and landed on the ground, there was an audible gasp from, you know, I’d say the majority of the residents that were there.

STEVIE: “The moment Oisín touched Irish soil, he immediately aged 300 years that he had missed in Ireland.”

McGINN: So they had been following the story, you know, cognitively, even though maybe their body language might not have suggested. For me, that was, kind of, a light went off my head because I’d spend enough time watching them watch TV. And I saw no response. Within three, four minutes of the robot telling them a story, you see something. And I think that, you know, my eyes are being opened to the possibilities here of what this could do.

FAKE: It’s interesting because out in Silicon Valley, we see very many people designing things for, you know, it’s kind of these engineers who are in their 20s and 30s. And they look around and they, you know, people have told them repeatedly that you should build something for yourself.

McGINN: Yeah. Yeah.

FAKE: And so you end up with all of these products that are geared towards, you know, urban single dudes, frankly. And you don’t see a lot of eldercare products – which, you know, if you just look at demographics, that’s sort of where the need is. And so it’s really, I mean, I think it’s really reassuring, actually, to see this kind of development happening.

McGINN: That’s really kind of you to say. And I think that there have been people who’ve tried it. I think they’ve failed for the most part.

FAKE: Why?

McGINN: I think that they … you kind of alluded to it. I don’t think they understand their users very well.

FAKE: Yeah.

McGINN: I think that, you know, from our perspective, like being able to live in a place like this and spend time in a place like this and be very actively involved with the users and engage them like, you know, we were here five times before we had a robot here.

We’re not doing this because it’s easy. Like it would’ve been a lot easier for us to build a robot and put it in a shopping center or, you know, put it in a bank or whatever it might be. It’s fundamentally, I believe, it’s worthwhile. And it’s that sense that we’re doing something good here

FAKE: Well, it’s human care. I mean, there couldn’t be much more significant work than that.

FAKE: It’s often said that we judge a society by how well or how poorly it treats its weakest, most vulnerable members. Whether or not we use robots in nursing homes to assist or replace us as humans, it will also tell us how we care for each other and who we are.

Look, I don’t get to decide should this exist? And neither does this show. Our goal is to inspire you to ask that question and the intriguing questions that grow from it.

LISTENER: What’s gone wrong with the human labor pool? Why can’t we retain humans to do this job of caring?

LISTENER: If I’m offered robot care, will I feel unworthy of human care?

LISTENER: And what happens when I’m gone? Will my robot have bonded with me and then someone else just gets my robot?

LISTENER: Talking to a robot, no thanks. Can someone please tell me what’s wrong with watching Netflix all day?

LISTENER: The robot could interview me…

LISTENER: But I want a human to be with me because they’d understand me much more.

LISTENER: Do I have a robot on call 24/7? It can come, you know, play video games with me or something. Or is it the sort of thing where I gotta sign it out? I don’t want to deal with any more sign-out sheets when I get older.

FAKE: Agree? Disagree? You might have perspectives that are completely different from what we’ve shared so far. We want to hear them.